9780712352529

British Library, 2019

318 pp

paperback

Not to steal thunder from either this book or the British Library, but ever since Valancourt came out with their first

Valancourt Book of Victorian Christmas Ghost Stories, I've sort of made it my yearly mission to read this type of thing around Christmas time, in a very small way carrying on a tradition which, as the editor of this volume notes, began orally, changing to print in the early 1820s. (Speaking of Valancourt, Dr. Tara Moore, who edited the above-mentioned book, also offers her thoughts on the matter in a 2018 podcast, which you can find

here.)

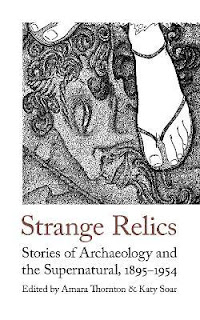

As you will notice from the cover photo, this is yet another volume included in the British Library Tales of the Weird series, of which I have become a huge fangirl. Believe it or not, I've actually had this book in my possession since August, but through sheer willpower I somehow managed to put off reading it until now, not an easy task. The good news is that it was completely worth the wait. Many hours of pure reading pleasure are to be found here, and I'm not exaggerating. The stories in

Spirits of the Season are all somehow connected to events that occur around Christmas time, and of the fourteen stories in this book, I had previously read only five: "The Four-Fifteen Express," by Amelia B. Edwards (1867), "Number Ninety," by B.M. Croker (1895), E. Nesbit's "The Shadow" from 1905, "The Kit-Bag," by Algernon Blackwood (1908), and "Smee," by A.M. Burrage (1929), leaving nine new-to-me tales to discover, which is always a good thing.

One thing I suppose I ought to mention is that not all of these tales are ghost stories

per se; as the title suggests, they are "Christmas hauntings," with more than just the shadow of the supernatural hanging over them. Another thing I should say is that it seems as if not all of these stories were written with a mind to scaring the pants off the reader, as evidenced by "The Curse of the Catafalques," by F. Anstey (1882), Frank Stockton's "The Christmas Shadrach" (1891), and most especially "The Demon King," by J.B. Priestly (1931), in which one particular scene had me absolutely giggling out loud. I think it's perfectly fine when good, supernaturally-tinged stories don't always end up on the scarier side; I also think that it's a pity that people often dismiss them simply because they didn't get the fright they expected, often missing the underlying points of the story. But enough of that.

My candidate for best story in this volume is M.R. James' "The Story of a Disappearance and an Appearance" from 1913. From what I gather while researching this one, it isn't among the most popular of James' stories -- more's the pity since it's quite the shocker. As the story begins, W.R., the narrator of this tale, writes to his brother Robert that he is unable to join him for the Christmas holidays because it seems that their uncle the Rector has disappeared, and that he has been called to join in the search for the missing curate. After a few days with no results and the police having left town, W.R. begins to accept the inevitable. In writing to his brother on Christmas day, he tells of a "bagman" he encountered who shares his thoughts on a "capital Punch and Judy Show" that W.R. must not miss "if it comes" ... which, in a way, it does all too soon, just not in the way one would expect. No antiquaries here. Read this one slowly, savor it, read it again, resavor.

The full table of contents is as follows, with starred titles new to me:

"The Four-Fifteen Express," by Amelia B. Edwards -- anthologized many times, but well worth the time once again

* "The Curse of the Catafalques," by F. Anstey -- snerk

* "Christmas Eve on a Haunted Hulk," by Frank Cowper, in which a man gets lost while duck hunting and lives through a horrific night

* "The Christmas Shadrach," by Frank R. Stockton. Light, a bit silly, but edging on the strange side with purpose. Beware of what you might find in a curio shop...

"Number Ninety" by B.M. Croker, one of my favorite ghost story writers; here the action takes place in a house no one will rent no matter how low the cost

"The Shadow," by E. Nesbit, another sad tale by this author

"The Kit-Bag," by Algernon Blackwood -- after a long court case involving a killer with a "dreadful face," the private secretary of the legal firm involved decides it's time for a vacation. Whether or not he'll get his kit-bag packed beforehand is another story.

* "The Story of a Disappearance and An Appearance," by M.R. James

* "Boxing Night" by EF Benson, in which dreams play the major role -- another example of the underlying story here being worth much more than the potential scare

* "The Prescription," by Marjorie Bowen -- although a wee bit predictable, still very much worth the read

* "The Snow," by Hugh Walpole, in which a wife learns the hard way that she should have listened to someone else's advice.

"Smee," by A.M. Burrage, a favorite of the Christmas ghost story circuit, with very good reason.

* "The Demon King," by J.B. Priestley -- the "stolid Bruddersford crowd" definitely gets its money's worth and more during a pantomime and the Happy Yorkshire Lasses make their debut dance appearance

* "Lucky's Grove," by H.R. Wakefield. This story came in second in my personal favorites lineup. The Braxtons' land agent finds and cuts down the perfect tree for their family Christmas celebration; unfortunately, no one bothered to tell him that he shouldn't have taken it from Lucky's Grove. A fine story this one, so much so that I'm actually considering buying a copy of the old Arkham House edition of The Clock Strikes Twelve to read more of Wakefield's work.

Spirits of the Season makes for great Yuletide reading, but if you missed it this holiday season, not to worry. It can be enjoyed just as much any time of the year, and for true fans of these old stories -- the famous and the "unjustly obscure" -- it is a definite no-miss. Editor Tanya Kirk has certainly made some excellent choices for inclusion here, and they are very much appreciated by this reader.

Just one more thing: for those who may not know, Ms. Kirk also has another volume of stories called

The Haunted Library, which picks up many stories that have never been anthologized. Buy button clicked. Expect more on that book to come later.