9780712354424

British Library, 2022

340 pp

paperback

It's time for another book in the British Library Tales of the Weird series. This time we're off to the remoteness of the Arctic and the Antarctic with Polar Horrors: Strange Tales From the World's Ends. My geek self has a particular fascination with the history of polar exploration, which after a while led to a particular fascination with fiction set in these locations as well, so this book is tailor made. With the exception of one story from 2019 that editor John Miller has chosen to include here, the remainder of the stories range from the 1830s through the 1940s, with the earliest in the section entitled "North," reflecting, as Miller notes in his introduction, the "earlier arrival of the Arctic than the Antarctic into European and American writing."

Surprisingly, there were only two stories that I'd read before, leaving nine here that are new to me. The first of these is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's well-known "

Captain of the Pole Star," followed by Harriet Prescott Spofford's "

The Moonstone Mass," in which a young man decides to attempt the Northwest Passage. About that one, all I will say is that anyone should think twice before setting sail on a ship named

Albatross, especially when heading into unknown territory. My favorite stories (in order of appearance) begin with

"

Skule Skerry" by John Buchan (1928), from his

The Runagates Club, which I own but haven't yet read. An island at "61° latitude in the west of the Orkneys" is where this story is situated. The narrator of this story is an ornithologist, Anthony Hurrell, one of a group of men at a gentlemen's club in London who regale each other with their stories. He had gone to the Norland Islands one year for the spring migration of certain birds, but unlike other people who "do the same," he had in mind something quite different. Taking his cue from prior research he'd done and using the Icelandic Saga of Earl Skuli as a guide, he'd found a reference to a certain "Isle of the Birds," which was located "near Halsmarness ... on the west side of the Island of Una." Further research nets a mention of

"Insula Avivum... quae est ultima insula et proximao, Abysso," by a "chronicler of the place." Intrigued, he made his way to Una, and finds exactly the place that had "been selected for attention by the saga-man," Skule Skerry. He is told that it has an "ill name" -- that "Naebody gangs there," and that "the place wasna canny." While highly atmospheric, it's really all about the journey in this one. Next on the list and deserving of top honors is the incredibly unsettling "

The Third Interne" by Idwal Jones (1938), which appeared in

Weird Tales in January of that year, listed as "A brief tale of a surgical horror in the Asiatic wastes of northern Russia." As Miller notes about this tale, the setting "outside the established limits of civilisation" is perfect for the secretly- unfolding of "darker enterprises." In this story, a group of three science "internes" who had studied under Pavlov set their sights on working with "a far greater scientific man than he," a certain Dr. Melchior Pashev, "a brilliant worker in neurology." Dr. Pashev, as "the third interne" relates, had once cut off a dog's head and managed to keep it alive for three years. It had "functioned beautifully," barking, drinking water, blinking its eyes "in affection," just like a normal dog despite the lack of a body. The three worked hard and saved the money they made in their jobs and finally borrowed enough to get them to Yarmolinsk, where Pashev was busy with his work. Welcomed warmly, after a while their devotion grows to the point where it knows no bounds. And that's about all I will say about this one, except that the ending turns things back on the reader, where he or she must judge between two alternatives. This is one of the strangest and most eerie mad scientist stories I've ever encountered, and not only gave me the shivers but made me feel queasy. Also deserving of high marks is John Martin Leahy's "

In Amundsen's Tent" from 1928, a story of an horrific series of events left behind in an account "set down" by Robert Drumgold, a member of the Sutherland expedition aiming to be the first to the south pole at the same time that Scott and Amundsen were vying for the same honor. It begins with a question that asks

"What was it, that thing (if thing it was) which came to him, the sole survivor of the party which had reached the Southerrn Pole, thrust itself into the tent, and issuing, left but the severed head of Drumgold there?"

Having discovered and read the journal left behind by Drumgold, the narrator of this story and his comrades had decided to suppress the parts that dealt with "the horror in Amundsen's tent," so as not to "cast doubt upon the real achievements of the Sutherland expedition." But he's decided that it is now time to release it to the world, and thus his story of horror begins. Don't be surprised if you find something familiar in this one.

Three more stories of note, presented here in no particular order, deserve a mention. Although modern (2019), Aviaq Johnson's " Iwsinaqtutalik Pictuc: The Haunted Blizzard" is a reminder that there is more than a measure of truth in indigenous legends, which in this case, have seemed to have been forgotten by all except children and elders, with disastrous consequences. I am always happy to see indigenous literature in any volume, so cheers to the editor. "A Secret of the South Pole" by Hamilton Drummond (1901) begins with a visit to a former sea captain during a downpour. The captain loved to tell stories, and on this day, what he's about to say has to do with a strange artifact he calls "the gem of my whole kit." If any one could tell him what it is, he has offered to give that person "the whole shanty." All he knows about it is that it's "a bit o' the South Pole" and launches into a story about how it came to be in his possession. Once upon a time he and two fellow sailors were stuck out in the ocean in an open boat, when they encountered a derelict ship and decided to go on board. As he tells his attentive audience, "what came after was queer, mighty queer, that I'll admit." No Flying Dutchman lore here, just weirdness. Mordred Weir's "Bride of the Antarctic" (1939) centers on an "ill-fated expedition" headed by "Mad Bill Howell," who had forced his wife against her will to go with him to the coast of Victoria Land. Legend has it that Howell was a cruel man, and during his expedition all perished during the long Antarctic night except Howell and the cook, who were both saved when the ship came to pick them up. Now another expedition has come to the same place, where strange happenings begin just as the winter darkness falls.

And now the difficult part, where I'm left with three stories that I just did not care for, but your mileage may, of course, vary. To be fair, they all certainly fit the bill of "Strange Tales," they are set at one of the "World's Ends," and the main characters of these stories did technically experience some sort of polar horror, each in his or her own way. Therefore, the editor did his job. But as a reader of the weird and the strange, these three just left me cold and unfazed. In my way of thinking, the opening story of an anthology should set the tone for what's to come, making me excited about getting to the rest. Unfortunately, that didn't happen here. "The Surpassing Adventures of Allan Gordon" by James Hogg started out well, but its novella length and a polar bear with the name of Nancy saving the main character's skin time after time just didn't do it for me. Quite honestly, this isn't the story I would have led with. "Creatures of the Night" by Sophie Wenzel Ellis and Malcolm M. Ferguson's "The Polar Vortex" are, like "The Third Interne," tales which concern themselves with rather outré science for the time, but while Jones' story had the power to seriously disturb, these two were lacking in that department.

|

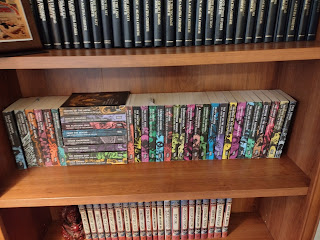

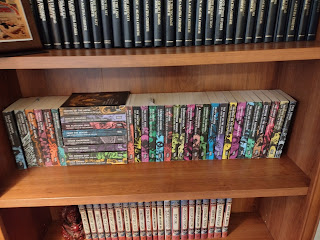

| from my own designated British reading room |

That's the thing about anthologies, though -- they truly are a mixed bag so you don't know what you're going to get. The eight stories I did enjoy were still well worth the price of the book, so I can't complain too much. And then there's this: I've read and loved two other anthologies in this series edited by John Miller (Tales of the Tatttoed: An Anthology of Ink and Weird Woods: Tales From the Haunted Forests of Britain) so if I wasn't exactly enamored with three stories in this book, he's still provided me with hours and hours of solid reading entertainment, as has the series as a whole.

Recommended.