9781905784356

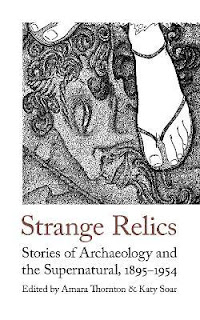

Tartarus Press, 2024 (first Tartarus edition 2000)

originally published 1951

289 pp

hardcover

I hadn't actually planned on reading this book this summer, but I had recently finished reading Circles of Stone: Weird Tales of Pagan Sites and Ancient Rites (ed. Katy Soar) as part of my ongoing reading of the British Library Tales of the Weird series and as it happens, that book began with an extract from Ringstones. I realized that unlike the other authors whose stories were included there, I'd never read anything by Sarban, so I bought this volume from Tartarus Press and immediately on finishing it, wondered out loud how the hell I had not read him before. I had already purchased the Tartarus edition of The Doll Maker and Other Tales of the Uncanny (2022) but once again, meeting the same fate as many books I buy, it had arrived, was shelved and other books came along that left it just sitting there -- as it turns out, a hugely serious, serious mistake. Let me just say that after finishing Ringstones, the very first thing I did was to pick up The Doll Maker and devour it, after which I immediately ordered Sarban's The Sound of His Horn and Other Stories, which arrived earlier this week.

|

| First edition, 1951. From ABAA |

I won't offer much in the way of author biography of here -- that is best discovered by reading Mark Valentine's excellent Time a Falconer: A Study of Sarban which I also bought directly after finishing Ringstones. It was originally published by Tartarus in 2010, although I picked up the paperback issue from 2023. John William Wall spent his working life in the British diplomatic service, and it was early in 1948 on a visit to England when he gave his future wife Eleanor two stories he'd written earlier in 1947 while working in Casablanca, "A Christmas Story" and "Ringstones." She found a publisher, Peter Davies, and to make a long story short, eventually Wall added three more stories, "Capra," "The Khan," and "Calmahain," and his first book was published in March of 1951 under the name Sarban. According to Mark Valentine, Sarban wrote to Mike Ashley that he had "had a liking" when he was young "for stories of fantasy and the supernatural -- H.G. Wells, and Walter de la Mare, for example," which had "prompted" him to "choose that vein" when attempting "something of my own (57)". Trust me here, he succeeded.

The best way to describe this book and its contents is to quote a small portion of the dustjacket blurb, which originally came from one of the book's "original reviewers" who said that these stories

"have a curiously-imparted quality of strangeness; the feeling of having strayed over the border of experience into a world where other dimensions operate."

Like the very best examples of the weird tale, Sarban's work tends to begin in normal circumstances while slowly but surely taking the reader across that border into unexpected and disturbing territory.

The opening tale in this collection, "A Christmas Story," carries more than a tinge of melancholy, but signals to the reader that he or she is about to delve into the realm of the strange. It begins on a "hot, damp Christmas Eve" in Jeddah as a group of British diplomats dress up and make the customary "round of calls" which includes a stop at the home of Alexander Adreievitch Masseyev, a Russian exile who now works for the Arabian Air Force. A bottle of Zubrovka labeled with a picture of the "European bison which seems to be the trade mark" sparks Masseyev's bizarre story about an experience he had in 1917 while a sea-plane pilot aboard a ship heading to Archangel. He and his friend were assigned the task of flying the plane to drop a message to a station where the ship was supposed to have made a call and could not due to dangerous ice conditions. Of course, things go awry, the plane goes down, and the two decide to walk through the marshes of the "immense, sad taiga" to civilization, no easy feat as winter is closing in. Luckily, they come upon a group of Samoyed hunters whom they believe will lead to them "to the nearest Christian men," but they encounter something entirely unexpected. As Masseyev notes, "Yes, there are rare things in Russia," and of all people, he ought to know. About "Capra" which I also quite enjoyed, it's best to say as little as possible, except perhaps that it's not too far a distance from the modern world of the 1920s to the realm of the old gods, especially when one is in Greece. Set in England during World War II, in "Calmahain" two young teenaged children of the Maple family, Martin and Ruth, whose lives are tightly restricted by the adults in their home and who are told repeatedly to stay in their own garden find a refuge in a game they play called "Journeys." It means leaving their yard, but as neither is likely to tell on the other, the game is on. They set a time limit that takes advantage of Mrs. Maple's "elastic after-breakfast hour with a detective novel," and each goes his/her own way. The idea is that when they next meet, they will describe the fantastical journey each has made, and the journey becomes a fantasy tale to share with the other in great detail. At the end of this particular adventure, Martin relates his travels but it's Ruth's story that takes center stage here, with Martin praising hers as "the best you've ever told." He adds that he doesn't know how she made it all up, and her reply is that she didn't "make it all up." Absolutely excellent story, one you may want to read a second time once you've finished it. Correction -- you should read it again. Of all of the stories in this book, it is "Ringstones" that clearly wins the prize for most disconcerting, and it happens to also be my favorite. Steeped in antiquity, in mythology and an added darker layer of subjugation and dominance (which seems to be part of Sarban's repertoire, as I noticed in The Doll Maker, but more on that book another time) it most strongly continues the thread of straying "over the border of experience" into another world altogether. Two friends, Piers and the narrator, have a conversation about Piers' good school friend Daphne Hazel, who has taken a summer job as a tutor/au pair taking care of "some foreign kids," specifically a teenaged boy and two younger girls. Their discussion includes commentary on Daphne's sanity, with Piers mentioning the fact that she wouldn't be likely to "have come under influences that would encourage the germination of elvish fancies and eerie illusions" at the school she is attending, and that he would be "much more likely to spin fairy tales for the fun of them than she is; and yet." Piers asks his friend to read the contents of an exercise book that Daphne had written and sent to him, and it's only the next morning when the two friends talk about it that the significance of the state Daphne's mental health becomes clear. At first it begins as a relatively benign story detailing her arrival at Ringstones Hall in Northumberland, meeting the children Nuaman, Marvan and Ianthe and well as some of the outdoor games they play while her employer spends time on his research. Soon, however, what sounds almost idyllic slowly turns dark and menacing as Daphne discovers that there's much more to this boy than she could possibly realize, and that she may "never come to the end of Ringstones." I'm being purposely vague here because you really must read this story to feel its full impact, and nothing I say can even come close.

While I enjoyed some of the stories in this volume more than others, what travels through all of them is the author's imagination and striking prose style that slowly and unexpectedly moves the reader into darker realms. He raises the storytelling bar as he adds in elements of mythologies and the natural world that complement each other as well as the characters who populate his stories, all the while building in layers of the mysterious and the strange to create different worlds where, as he notes in "Ringstones," "some queer feet have danced." This creative blending that marks his work as truly something of his own makes for compelling, unforgettable and unputdownable reading that stuck with me long after the last page had been turned.

Beyond highly recommended -- truly a collection I will never forget.