Tuesday, April 1, 2025

Tales of the Coming War, by Eric Stener Carlson

Sunday, June 23, 2024

Ringstones and Other Curious Tales, by Sarban

|

| First edition, 1951. From ABAA |

"have a curiously-imparted quality of strangeness; the feeling of having strayed over the border of experience into a world where other dimensions operate."

Like the very best examples of the weird tale, Sarban's work tends to begin in normal circumstances while slowly but surely taking the reader across that border into unexpected and disturbing territory.

Wednesday, July 19, 2023

Caged Ocean Dub, by Dare Segun Falowo

|

| from Intercontinental News |

The final section of this book is "Heralds," and these stories are given over to an entirely different style, moving into the realm of science fiction, largely futuristic in nature. "What Not to Do When Spelunking in Ananmbra" left me with goosebumps and cold chills crawling up my spine. A "rogue speleogist" discovers a "new cave system" that tells the future in "terrifying etchings that glowed as if alive," also offering "ancient impressions of alien life" that will have "an impact on our futures." And that they do, just not in the way originally he predicted. As this story winds down, the realities of the future become outright frightening. Also frightening but absolutely gorgeous in the telling is the novella-length "Convergence in Chorus Architecture", a sort of Nigerian weird combined with speculative fiction approach complete with world building which truly begins with a lightning strike. When "slow lightning touch[es] the heads of Akanbi and Gbemisola" with "small bright hands" while they are in the water, they are brought back to their village where it is determined that they are "dreaming vivid," having been "called on to see." A particular potion is brewed that allows the rest of the community to follow the lightning victims into their "shared dream." What happens afterward I won't say, but the story as a whole incorporates shamanistic elements along with strong mythological ties, magic and the power of dreams that culminate in a spectacular and breathtaking finish.

"were mostly inspired by real events and/or emotional states, and were also fuelled by my love of indigenous cosmologies and pop culture symbolism. They were written in various caged spaces, where the pulse and ambient sounds of the world outside became, after a while, like arrhythmic waves crashing on the shores of my listening."

Tuesday, March 14, 2023

Dark Arts, by Eric Stener Carlson

"Art is illuminating, but there's also something dark about it -- something menacing, magical, obscure ... a conjuring of sorts, a reaching beyond the circle of the campfire, a groping of sorts, a reaching beyond the circle of the campfire, a grouping for dangerous things hidden in the faintly-perceived undergrowth."

As the dustjacket blurb notes, art is also a "spirit board" that allows his people to "contact shades from the past, or to discover danger in the shadows."

While I could certainly write great things about each and every story in this book, I'll have to settle for just a few of my favorites in the interest of time and space. In "Golden Book," the collection's opener, a woman makes contact and finds connection with a young girl in a library in Thailand while introducing her to a completely different understanding of the afterlife. Up next is "Bradycardia," a reality-bending (and pardon the phrase from the psychedelic 60s), utterly mind-blowing stunner of a tale which you will want to reread straight away before even thinking about going on. The subject of this story is a successful editor whose work has allowed him to "shout into the void" a number of "new voices," but who is also plagued by a debilitating series of nightmares of being on the editorial board of a company that has published some really crap hack material. Reality is interwoven with vivid dreamscape here as well as the "contradictory images" that keep floating through the editor's mind, and just when you start to wonder what the heck might happen next, Carlson provides a most shocking, unexpected and horrific ending to it all. "Salt" is a redacted transcript of the interrogation of a professor who enjoys witty rebus puzzles and who, like the character Campbell in Vonnegut's Mother Night (mentioned more than once here and throughout Dark Arts), believes in his own form of a "Kingdom of Two" -- "a closed circuit" where he and his wife are deeply in love, and

"thought for each other, lived for each other. We would finish each other's sentences, were probably thinking each other's thoughts..."

and, as he says, came to develop other distinct ways to communicate with each other so as to "avoid detection" -- a "triple layer of communications" -- when she first drew him into the world of espionage. As he lays out their life together including the birth and death of their son (with whom he can still supposedly communicate afterward) his interrogator drops a bombshell that very likely changes this man's life completely, and yet, because "all those messages have to count for something ... some greater meaning," the show must go on.

|

| from Circady |

Eric Stener Carlson is an incredibly gifted writer who never fails to offer a deep, enriching and soulful quality in his work which illuminates the humanity of the author's characters no matter where they exist in the world. Like the best of the best weird tales, the stories in Dark Arts reach that certain point where people in the mundane world find themselves at some point having crossed a threshhold into a completely different reality; like the best authors, Carlson's skill is in illuminating the challenges of his characters who must make their way through what he describes as the "dark spaces" that are "intertwined with life and death and art." At the same time, it seems to me that one major idea that he never loses sight of throughout this book is that even in the darkness there will continue to be love and hope that may help to offset the horrors found there, so very much the case in our current world. Dark Arts is a truly excellent collection, both beautiful and terrifying, written by a skilled master of his own art. Beyond highly recommended, I cannot praise this book enough.

Friday, December 17, 2021

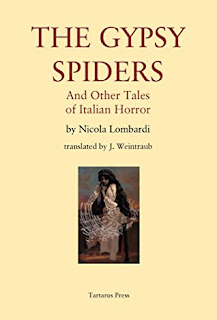

arachnophobes beware (part 3): The Gypsy Spiders and Other Tales of Italian Horror, by Nicola Lombardi

"He had lived next to death for months, side-by-side with it, and now that he had managed to escape and find shelter in, for him, the safest and most beloved place on earth, he realised that the horror had only preceded him there, to welcome him home."

But what he hasn't realized is that the true horror is only beginning.

In "Alina's Ring," a wounded soldier wakes up to discover himself in a farmhouse, being taken care of by a young woman named Alina. He notices that "there was something not quite right" in her eyes; and that she "was determined to unburden herself of the thoughts that were cascading through her mind." As they talk, he's looking for a "way out" -- and about this story I will say no more. "Sand Castles" finds an elderly man returning to his beloved Villa Dora which he'd been away from since 1945, at age nine. As Italy was "being rebuilt," his family took him to Bologna, where he'd rebuilt his own life right on through to retirement. Now in his mind, it is time to go back to the Villa Dora, to give "destiny the chance to complete the plan designed for him." When he finally arrives, he hears his old childhood pals "calling out his name..." Weintraub notes that in these stories, it's "the actuality of the war and its aftermath that lead to madness, obsession, and significant 'collateral damage'," and in these three stories, all of these elements scream loudly from the page.

Six incredibly dark stories remain in this volume, nearly all of which are gut-level disturbing and much darker than I normally tend to go in the realm horror fiction, but god help me nothing short of a bomb blast in my living room would have made me put the book down while reading them. I'll mention two here. First, "Professor Aligi's Puppets," in which a young boy's fascination with puppet theatre takes a turn into nightmare territory, and "Striges," my favorite story in the book, which thoroughly chilled me to my bones. In that one, a man looks back in time to recall something he'd witnessed in his childhood that left a "kind of knotting" in his stomach (a similar reaction to my own with each step of this story, by the way) when he thought about his friend Francesco, the "prisoner of a situation so horrible its true nature could hardly be fully understood." As kids, Francesco and his friends were fascinated with spiritualism, flying saucers, divination and "on and on," fueling their imaginations with comic books, television, horror novels, movies etc. The trouble begins when Francesco reveals to his buddies that his mom is writing a "study on witches," and would be going on a trip throughout Europe. As the narrator recalls, the boys got a bit of a charge over that, knowing that "whatever she might bring home would launch us further off the face of the earth," before offering his observations in hindsight that "she would be bringing us the burial, once and for all, of our childhood, and much worse."

Wednesday, July 28, 2021

A Maze for the Minotaur and Other Strange Stories, by Reggie Oliver

|

| "The Wet Woman" (p. 49), illustration by Reggie Oliver. |

"Oliver's work is notable for its style, wit humour and depth of characterisation, and also for its profound excursions into the disturbingly bizarre and uncanny"

and I have to tip my hat to this man who's given me so many hours of reading pleasure over the last few years, and to Tartarus as well for bringing forth this eighth volume of Oliver's stories. It is definitely one not to miss whether you are a regular fan of Oliver's stories, or a reader drawn to the realm of the strange or the weird. Don't be surprised if you find yourself feeling a bit off kilter after reading this book -- it's part and parcel of the Oliver experience.

most highly recommended.

Sunday, February 28, 2021

The Collected Connoisseur, by Mark Valentine and John Howard

"What we seek, and what we also half-fear, is all around us, always, had we the necessary calm intentness to discern it. "

"connoisseur of the curious, of those glimpses of another domain which are vouchsafed to certain individuals and in certain places."

The Connoisseur is a nickname given to this man by Valentine, who with the Connoisseur's consent, "dependent on anonymity and all necessary discretion," recounts "some of his encounters with this realm. " The narrator notes that while the Connoisseur is far from wealthy, he "supplements a decent inheritance" with "administrative work," he "shuns many of the contrivances of modern living," and is therefore able to indulge in a "keen pleasure in all the art forms." He is a seeker of knowledge and a walking encyclopedia of the arcane; if there's something he does not know, he knows any number of people to whom he can turn for answers. The mysteries he encounters are often built around some sort of cultural artifact either in his possession or brought to his attention, for example, in the first story "The Effigies," the narrator is looking at a "dark earthenware jug of quite perfect form" on the Connoisseur's mantel, sparking a story about his friend's visit to its creator, Austin Blake, renowned maker of "amphorae and delicate vessels" who had suddenly stopped producing at the height of his fame. There are also a few occasions in which Valentine accompanies the Connoisseur and witnesses events firsthand.

"These then, the wondrous, the spectral and the aesthetical, were the airs floating around me when I began to think whether I could go one step further than reading, and try writing, the sort of fiction I enjoyed."

It is this sense of the "wondrous, the spectral and the aesthetical" that he and in the last few stories, John Howard capture here in a style that reflects the writing of those previously-mentioned authors who came before, but still manages to remain quite original. Not everyone can carry off the voice of times past in his or her writing, but here it is pitch perfect. The last six of these stories were collaborations between the two authors, and anyone who's read the work of John Howard will recognize his style immediately. These tales are also a bit more fleshed out, with a bit more action involved, and provide a great ending to this collection.

I loved these stories, all of which on the whole offered days of fascinating reading, but of course and as always there were a few that stood out. "In Violet Veils" is probably my favorite of the collection, in which an experiment in the "revived art of the tableau vivant" results in a warning by the Connoisseur that

"such curious re-enactments were not to be essayed without some peril of affecting, in unforeseen ways, those involved: who could tell what might result from such a hearkening back to the original power of the mythological image portrayed?"

He knows whereof he speaks, having experienced firsthand an eventful, bizarre tableau vivant in the past. "In Violet Veils" has the feel of the decadent/symbolist literature I love to read, with more than a touch of the weird that gives it an extra edge of eerieness. In "The Craft of Arioch" the Connoisseur relates to Valentine his strange experience during a "walking holiday" in Sussex with his cousin Rebecca. Having left "the high roads and the dormitory towns" and traveling the "winding roads and nestling villages," they eventually find themselves at a barn where they expect to find hand-crafted rocking horses. Let's just say after a ride on a "cross between a horse and a white dragon," and "a winged cat with preternaturally pointed ears and peridot eyes," they return from "unknown regions" and "a plane of experience different to anything we may find in this world." "Sea Citadels," "The Mist on the Mere," "The White Solander" and "The Descent of the Fire" round out the list.

At the beginning of "The Secret Stars" The Connoisseur in conversation with Valentine notes the following:

"What we seek, and what we also half-fear, is all around us, always, had we the necessary calm intentness to discern it."

The Connoisseur's "rare glimpses" are the very heart and soul of this book.

The Collected Connoisseur is one to read curled up in your favorite reading space, hot cup of something or other in hand. Like the Connoisseur, I am quite partial to Qimen/Keemun tea; I am also one of those people described on the back cover blurb -- "the lover of esoteric mystery and adventure fiction. " More to the point, I am also in complete awe of Valentine and Howard's visionary writing here and elsewhere. Every reader of the weird, the fantastical, and of the occult should have The Collected Connoisseur sitting on his or her shelves. No collection would be complete without it.

Friday, November 20, 2020

"a different domain: " The Nightfarers, by Mark Valentine

"We enter them, and a sense steals over us of being in a different domain."

The best writers, in my humble reader opinion, somehow manage to deliver stories that shut out the sensory realm altogether and deliver me fully into the world(s) that they've created. That's certainly how it is in the case of The Nightfarers, in which the author's elegant, atmospheric and often ethereal writing takes you into (again quoting from "The Axholme Toll")

"...places which have their story stored already, and want to tell us this, through whatever powers they can..."

"I am by nature solitary and prefer nothing better than quietness and my own company, with a good fire and a good book."

I did have to laugh when I started reading The Nightfarers, a timely coincidence since when I started it I was eagerly awaiting news of the winners of both the National Book Prize and The Booker Prize. The first story, "The 1909 Prosperine Prize," begins with several judges who have come together to decide who will win that award. The shortlist for this literary award comes down to seven entries (Algernon Blackwood, Marjorie Bowen, William Hope Hodgson, Bram Stoker, 'Sabazeus', and MP Shiel), but it seems the judges cannot make up their mind. The secretary's plan to push through the indecision is nothing short of genius. Major book love going on not just here, but in several of the other stories in this volume. "White Pages," for example, finds a lover of "obscure old books" actually finding a sought-for, "very scarce" book called Invisible Friends, so-named for a reason, while in "Undergrowth," a man who wants to be left alone while browsing bookstores without any help from the proprietor finds himself eventually roaming through books on his own in a rather unique way. I had to read this one twice just to make sure that what I thought was happening was happening. This story is a little gem, but there may be something in the advice given in "The White Pages" in terms of riffling the pages of any book you might read before starting it. The rather ethereal "The Inner Sentinel" is a story in which the narrator finds himself piecing together "some hints of a vast history" in his dreams which become more than a feeling that he's "lived another life" in the space of sleep. This one is absolutely beautiful, transporting me into the narrator's visions as life outside of myself faded to nothing; it is also as the author notes in the "About the Stories" section of this book, "a tribute to William Hope Hodgson's The Night Land. "The Bookshop in Novy Svet" was another story that made me do a double take at the end, another absolutely brilliant work featuring an actuary, a bookstore owner, an artist and dying poets, all the while reminding me for some reason of Meyrink. Hmm. I think it's pretty obvious by now that I absolutely loved "The Axeholme Toll," which begins with a mention of Robert Louis Stevenson's "The Merry Men" leading to talk of "enclaves within the solid land of the country, which are islands in a different sense."

Of the remainder of the stories, the eerie "The White Sea Company" also falls into the favorites category, as does "The Dawn at Tzern" and "The Seer of Trieste." The others I haven't mentioned due to time considerations, "Their Dark and Starry Mirrors," "A Walled Garden on the Bosphorus" and "The Mascarons of the Late Empire" are all atmospheric pleasures which carry the feel of the fantastical, while "The Box of Idols" is a short but fun little supernatural detective story.

While it's a hard book to pin down as to category (and I don't think it needs to be) The Nightfarers is an exquisite collection of stories from a writer of incredible genius and talent. These stories should appeal to those readers who enjoy tales about what lies hidden underneath or alongside the material world that only a few rare people will ever experience, as well as to those readers who prefer being caught up in atmosphere rather than simply focusing on plot. I can't recommend this one highly enough.

Thursday, July 2, 2020

Unholy Tales, by Tod Robbins

Tartarus Press, 2020

291 pp

hardcover

I don't know what inspired the powers that be at Tartarus Press to put out this volume featuring stories written by Tod Robbins, but it was more than a great idea. Megacheers to you.

Robbins' work may not be familiar to everyone (it certainly wasn't to me before reading Unholy Tales) but the 1932 film Freaks directed by Tod Browning, based on Robbins' short story "Spurs," is a movie which is regarded "as a classic, or at least a cult favorite." And speaking of movies, another Robbins story in this volume, The Unholy Three was made into two different film versions: a silent (also directed by Browning) in 1925 and a 1930 remake which was, as Jeff Stafford notes at TCM, Lon Chaney's "talking picture debut, and ironically, what would prove to be his final film."

After the in-depth, not-to-be-missed introduction "Tod Robbins: An Unholy Biography" by a very knowledgeable Jonny Mains, Unholy Tales brings together the above-mentioned "Spurs," as well as three of four stories from Robbins' 1920 collection Silent, White and Beautiful: "Silent, White and Beautiful," "Who Wants a Green Bottle?," and "Wild Wullie, The Waster."

|

| original edition, from LW Currey |

Rounding it all off, pretty much the last half of this book is given over to The Unholy Three, published in 1917.

|

| original 1917 edition, from Biblio.com |

The Unholy Three is definitely the jewel in this crown. It is an extraordinary piece of pulpy crime fiction with a supernatural-ish vibe. I use the term "extraordinary," as I am huge fan of crime fiction from this era and have read (and continue to read) a wide variety of books filled with what I call sweet pulpy goodness, but never have I come across anything like this story, which sets a new bar for me in that zone. As with "Spurs," Robbins begins The Unholy Three at a circus, where Tweedledee (in the movie described as "Twenty inches! Twenty years! Twenty pounds!") sits contemplating the day "Men would fear him! and he would read this fear in their eyes." It's his small body,

"this caricature that made him a laughing-stock for the mob to jibber at, that turned his solemnity of soul into a titbit of jest for others, his anger into merriment, his very violence into the mimicry of violence"that keeps him from being "taken seriously." But deep within his soul burns an "insatiable fire" that produces "scenes of violence" and visions of a "new transformed self" in which he would be feared, with an audience that would "tremble at his villainy." Along with his fellow circus friends Echo the ventriloquist and Hercules the strong man, he grabs his chance to turn his visions into a reality. A word of advice: don't watch the movie and think you've read the book. As much as I enjoyed both versions, neither holds a candle to the original text.

|

| Harry Earles, from Freaks. Earles also played Tweedledee in both versions of The Unholy Three. From IMDb. |

Moving on ever so briefly (so as not to spoil) to the short stories, "Spurs" reminds me so much of the French contes cruels that I love. As in Freaks, a circus love triangle is at the center of this story of revenge. M. Jacques Courbé, a man of twenty-eight inches, had fallen in love with Mlle. Jeanne Marie the bareback rider the first time he'd seen her act. She, however, has eyes for the "Romeo in tights" Simon Lafleur, her partner, and views Courbé's attentions and utterances of love as a "colossal, corset-creaking joke. " The wheels in her head begin to turn when Jacques just happens to mention that he has been left a large estate and that he has plans to turn her into a "fine lady" if she will marry him. Trust me on this one, she should have most definitely said no. Not quite as grotesque as the fate of Venus in the film, but still beyond bone-chillingly horrific. "Silent, White and Beautiful" also falls into the realm of the horrific, as an artist returns to France after a depressing attempt at a career in America, where his art fails to sell. On his return he hits on a solution as to how to make his work as life-like as possible. After a nonstop reading session of these two stories which open the book, I was very much ready for a wee bit of humor in "Who Wants a Green Bottle?," which examines what happens to the soul of the Lockleavens after they've left this world. I must say, this is one of the most ingenious and original wee folk stories I've ever read. Last but definitely not least is "Wild Wullie, The Waster," which is also a story of death and the afterlife but with a twist (or two) I'd not encountered in other ghost stories.

The question that opens this book is this:

"How does an author fêted as equal in genius to Edgar Allan Poe disappear into relative obscurity?"Unfortunately, that seems to be very much the case with a number of writers of yesteryear whose work I admire. Where Tod Robbins is concerned, though, I've taken the first step onto that "path to becoming a fervent worshipper of a deliciously twisted writer who knew how to keep his readers more than entertained" mentioned at the end of Mains' introduction. Two more books of Robbins work arrived yesterday, I bought and made time to watch all three films I mentioned above, and I am certainly recommending Unholy Tales to anyone who will listen. Deliciously twisted writer indeed, and I can't get enough.

Friday, April 3, 2020

The Child Cephalina, by Rebecca Lloyd

Tartarus Press, 2019

260 pp

hardcover

"One mistake begats another in those folk who are blinded by their own desires."

Mid-century Victorian London is the setting for this thoroughly disquieting but captivating novel which will not release you from its grip until you've read the very last word. Even then it may take some time; it is so cleverly done and so unsettling that in my case, it was impossible to stop thinking about it long after I'd finished.

Narrator Robert Groves is a bachelor living in a house near Russell Square. With the help of his housekeeper Tetty Brandling and a young boy by the name of Martin Ebast, he's spent the last three years interviewing "children of the streets" as part of his research for his forthcoming book Wretched London, The Story of the City's Invisible Children. Every Sunday Martin rounds up and brings a small group of these children to Groves' house on Judd Street; it is on one of these days that young Cephalina first appears. It is apparent to everyone that she isn't a part of that day's group of "nippers;" the first things Tetty and Martin notice are her clean, recently-washed and plaited hair as well as the "slender and white" hands that are "delicately formed" and obviously unused to street dirt or hard work. Groves is more than fascinated, Tetty is suspicious, and Cephalina offers little information about herself except that she lives in Hackney with her guardians the Clutchers, for whom she does some sort of work and that she has a twin she calls "E." When she returns to Judd Street a second time, she adds a bit more to (and changes part of) her story; further visits with Robert reveal a bit more about her life with the Clutchers and a strange bond develops between the two. In the meantime, Tetty has enough on her plate dealing with the stress caused by an embarrassing lack of funds required to run the household, and the tension between Tetty and Robert escalates as Tetty tries to warn Robert about the "sordid child," who has "too much knowing about her" and he refuses to listen. He credits her fear to her "superstitious nature," failing to notice just how deeply afraid she is of Cephalina. Ignoring Tetty and her warnings, his obsession with and devotion to the young "waif" grows ever stronger, as does his desire to help her, which in his own words, leads him to a "sorry mess indeed." That is seriously all I'm going to say about the plot -- it's better to go into this book knowing as little as possible.

I normally shy away from modern writers' work set in Victorian England, because I'm a huge reader of Victorian fiction and some of these people just do not get things right. That is not true in this case -- Rebecca Lloyd has done great things here. Her depiction of Victorian London is striking, not just in her descriptions of the "dirty, grit-filled fog," the "stench of the Thames" or the "incessant din" that could drive a person mad, but she also captures the current mood of the city, for example, in the excitement over the new Crystal Palace, or the "giant wave of spiritualism" which had found its way into London over the past three years, along with its adherents, practitioners and critics. Her characters are substantial and realistic as individuals, but it's in the various relationships she's created between them where they thrive and give this novel meaning. But by far the author's greatest achievement is in her ability to keep the reader on edge as she cleverly puts together a story in which she has interwoven a number of things left unsaid, things kept hidden, misperceptions, misjudgments, and above all, the mystery of the enigma that is Cephalina. From the beginning she leaves the reader with the feeling that there is something a bit off about this strange girl, and continues to heighten our interest in her by revealing her story slowly and only in small bits at a time. The same is true in the slight scattering of clues that she leaves for the reader to follow to the chilling and shocking end.

I'm just a reader (and a casual one at that), not a critic, but I know when I've found something of quality and this is definitely it, a book that tells me that the author is indeed a master of her craft. The Child Cephalina at times feels like an old serial cliffhanger, and inevitably I read it into the wee hours of the morning, unable to put it down. It kept me guessing, very much on edge, and when that last page was turned at 4 a.m. I just sat there unable to even think of sleeping.

Very, very highly recommended. You will want to read this book. Trust me. It's unlike anything I've read before.

Tuesday, September 11, 2018

two beautiful books from John Gale: Saraband of Sable; A Damask of the Dead

"For do not we all wait for something that we know nothing of, something that has not arrived, and possibly never will." -- from "Vigil," A Damask of the Dead

A few months ago for reasons I still can't put my finger on, I picked up a copy of his Saraband of Sable from Egaeus Press (the third book in the Egaeus Press Keynote Edition series), never having read anything by John Gale before that time. Now I would read anything this man writes.

With absolutely no idea what to expect from this author on opening the book, it didn't take me long at all to realize that I had something exquisite in my hands. By the time I'd finished it, I was telling everyone and anyone who reads dark/strange/weird fiction that they need to buy a copy of this short but sophisticated, highly-satisfying collection of tales, not just because the stories are so good, but also because of the unique quality of the writing. I'm actually lost for words in trying to describe it, so perhaps I should refer to the description at Egaeus (from the link above) which says that

"Saraband of Sable presents eight of Gale's sumptuous strange tales; dreamlike at times, dense in their imagery yet delicate as dimming perfume."It also noted there that the author's "previous collections" ... "garnered praise for their sophisticated and decadent prose styling," and I'd only add that I found a sort of ethereal quality to his work, but it really goes much deeper than any description that my non-writer's head can produce. The most surprising quality of these stories, though, is that while basking in the sheer beauty of the writing, it's like the clouds lift and there at the heart of each story is the darkness that's been peeking through all along, finally emerging with gut-punching force. And while it seems that we're in the middle of long ago and far away, the essentially-human traits that are represented here are tragic, real and timeless. One more thing -- the incorporation of the natural world flows beautifully through each and every story, as in this description of a city's necropolis:

"... a few do venture here, to tarry for a while amidst the cypress and the ebony poplars, basking in the light which falls here like tarnished copper during the diurnal hours; they are the dreamers that revere the lank and elegant grasses that grow between the monuments of obsidian and chrysoberyl, the grasses that turn from jade to gold during autumn; and they love the jackdaws who inhabit the sable green of the elder yews and who often speak in the voices of the dead through eating the fruits of the trees that look like crimson pearls, the trees whose roots bind tight the ivory bones of the long departed." (from "Lord of the Porphyry Nenuphar").The truth is that even before finishing Saraband of Sable, I was so enchanted that I absolutely had to have more, so I tracked down a copy of the now out-of-print A Damask of the Dead published by Tartarus.

"The perfumes of the East suffuse these tales, of poets, lovers and kings who, despite the luxury and beauty of their surroundings, desire something beyond."Immediately we find ourselves standing at the gates of "Death's City", with "palaces with colonnades flooded with darkness, stretching away into infinity," moving later onto "a castle of many turrets that reared up from a cliff of dark rock," complete with "black tourmaline crypts," at some point reaching an "onyx-domed city." The fourteen stories in this book transport the reader completely out of this world and into others where sorcery is a natural part of life, where poets can really fall in love with the moon, or where the ghost of a king appears one night to give advice to his son and heir, and more.

Fantastical these stories may be, but they are not breezy tales with rewards at the end; as with Saraband of Sable, there is only tragedy, unhappiness, and darkness to be found within.

On the dustjacket blurb of A Damask of the Dead, Mark Valentine has this to say:

"As Machen has observed, literature consists in the art of telling a wonderful story in a wonderful manner. Few writers today acknowledge the need for either element. John Gale is someone who has mastered both."I couldn't agree more, and that goes for Saraband of Sable as well. John Gale is a rare find indeed.

So highly recommended that no scale exists for how highly I recommend these books.

Saturday, November 19, 2016

campfire reading, part one of two: Muladona, by Eric Stener Carlson

Tartarus, 2016

290 pp

hardcover

Trying to get myself mentally put back together after a few upsets over the last week or two, Larry and I just spent three days far from the madding crowd in a cabin in the woods. No television, no people, nothing but silence and the smell of oak trees -- an environment beyond conducive to mental health repair and reading, so read I did, perfectly relaxed while laying out by a roaring campfire. First book, this one, by Eric Stener Carlson, who is the author of one of my all-time favorite novels, The Saint Perpetuus Club of Buenos Aires (2009). This time he's given his readers the tale of Muladona, "a doomed soul transformed into the devil's mule," based in part on an old Catalan legend.

This story belongs to Vergil Erasmus Strömberg (Verge), who tells us at the beginning that years ago he'd promised never to reveal the story of what happened in 1918, but it seems that "recent events" have made it necessary to go back on his word. His tale takes place in Texas, 1918, as the influenza epidemic rages through the small town of Incarnation. He's a "sickly boy" whose world is pretty much confined to his house and his books, and those have to be smuggled in by a friend since Verge's father, a coldhearted and narrow-minded Scandinavian Protestant pastor, believes that "anything written after Dante's Inferno" is "pure debauchery." Verge's brother Sebastian also has an interest of which his father wouldn't approve -- he is fascinated with mythology, anthropology, and mysticism; he also has a keen interest in "magical transformations into animals," and keeps his forbidden collection of books under the floorboards of his room. When they were younger, they were also transfixed by others who would feed them creepy tales, and one of these centered on the legend of the muladona:

"...when a woman commits an impure act, she becomes the devil-mule at night. She chooses her victims just like the first one ... the liars, the gossipers, the bad, li'l kids. And you'll hear her comin' for ya at night, by the way she clanks the chains of hell."As the flu wreaks death and devastation throughout Incarnation, Verge, now 13, finds himself alone in the family home. His mother has been gone since he was seven, his father receives a telegram that takes him away from Incarnation to tend another pastor's flock, and Sebastian has run away from home with the idea of traveling "from reservation to reservation" across Texas to "record the stories of the elders before they disappear," as a volunteer doing ethnological surveys for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The woman looking after him also has to leave to take care of her sister, so Verge is left on his own. It isn't too long before he receives a strange telegram from his brother that at first Verge thinks is a joke, but in reality it is a warning that muladona is coming for him at midnight and an admonition to be prepared. And when the visit takes place, this strange creature from hell tells Verge that over the next seven nights,

"I will vi-isit you. Each night, I'll tell you a be-ed time story. Wrapped within the sto-ories are clues to the identity of the person who takes the form of this mi-ighty creature you see before you. A-any time you like, you can throw back the sheets and tell me who you think I am. If you're sma-art enough, Poof! I disappear, and you never have to see me again."If he fails to guess the creature's name correctly, the muladona promises, Verge will be dragged down to hell. And so the stories begin, as does Verge's torment while he tries to make sense of what he's hearing.

If I try to explain further, I'll wreck things for potential readers, but there is a LOT going on in this book, starting with the intolerance of the good Christian folk who stopped in Incarnation and made it theirs, relegating the "descendents of the natives" who formerly lived in the town's "grand old mansions" to the status of menial servants. As the dustjacket blurb notes, the story takes the reader "through the dark history of Incarnation, from the murder of the Indians by the Spanish settlers..." so beware -- it is not at all pretty. It's not too difficult to understand the subtext here, but the most interesting parts for me were the stories told by the muladona each night. Oh my god -- I already knew that this author is one hell of a writer, but I was completely sucked into each story, each one pointing to some horrific realities not just for Verge but also in their repeating themes that I'll leave for others to discover.

I will say that I am not a big fan of monster stories, but sheesh -- this one had me tied up in knots as I waited for young Verge to figure things out. And what's more, when I got to a part toward the end where Verge warns someone of the muladona's impending visit, it dawned on me that Mr. Carlson had set up a world here in which no one thinks our young lad is crazy, but one in which the existence of such a creature is just another part of the landscape.

Muladona is original, fresh, and above all, it is a thinking person's horror novel, which I genuinely appreciate. It's not some slapdash book that's been thrown together -- au contraire -- it is very nicely constructed, well thought out and intelligently written. I would expect no less from the author, whose The Saint Perpetuus Club of Buenos Aires is truly a work of genius. He continues that genius here. Don't miss this one -- mine is the hardcover copy, but there is an e-book available as well. Highly, highly recommended for readers who enjoy the work of excellent writers and for people who like their horror novels more on the cerebral side. This is a good one, folks.

Tuesday, June 14, 2016

Nightmares of an Ether-Drinker, by Jean Lorrain

Tartarus Press, 2002

247 pp

hardcover

"But I know that I play my part too. I make that dreadful hell myself; I, and I alone, provide its trappings." -- (128)

One thing before I post my thoughts about this book: my copy is from Tartarus, but Snuggly Books earlier this year released a very affordable copy (go ahead, click ... I reap no gain for each click from Amazon) making this book widely available for all.

now...

As I posted on Goodreads earlier, I had no clue when I first picked up Lorrain's Monsieur de Phocas that it would mark the beginning of my obsession with this author, and indeed, this entire school of writing. I also noted that Lorrain's work has a way of causing the outside world to disappear because I am so deep into his, a rarity for me. This collection of 27 short stories only cements that feeling.

Once again, I won't be going into any detail at all about any of these dark tales because, like the stories in The Soul-Drinker and Other Decadent Fantasies, they really are best discovered on one's own. The contents of this collection are divided into Early Stories (7), Sensations (9), Souvenirs (3), Récits (4) and Contes (4), and they are some of the best, darkest, eeriest works I've ever read.

Brian Stableford's excellent introduction to this volume offers the reader a look at not just the contents of these stories, but also a brief glimpse into Lorrain's somewhat troubled life. His stories here (and elsewhere) encompass what was at the time "sexual perversity," which as Stableford notes in another excellent work Glorious Perversity, cost him any chance of being translated into English and being noted as a "writer of the first rank in his own country." Luckily, Stableford himself has translated Lorrain's work, and as a bonus, he is an expert in the field of Decadent fiction.

Nightmares of an Ether-Drinker shows a very wide-ranging Jean Lorrain. As always, most his stories reveal, as one of his characters notes in "The Possessed," "the sheer ugliness and banality of everyday life that turns my blood to ice and makes me cringe in terror." (124). His Contes are just plain unsettling, taking place among the beauty and strangeness of nature, and his supernatural stories are dark, ambiguous, and caused no end of unease.

|

| from AZ Quotes |

One of the main themes in these stories, and the one that seems to crop up in all of Lorrain's writing, is the horror of the masque. As he notes in "One of Them,"

"The masque is the disturbed and disturbing face of the unknown. It is the smile of mendacity. It is the very soul of that terrifying perversity which understands depravity. It is lust spiced with fear, the alarming and delicious risk of throwing down a challenge to the curiosity of the senses. 'Is she ugly? Is she beautiful? Is she young? Is she old?' It is politeness seasoned by the macabre and heightened perhaps, by a dash of baseness and taste of blood -- for where will the adventure end? In a cheap hotel or the residence of some great demi-mondaine? Or perhaps the police station, for thieves also conceal themselves in order to commit their crimes. With their solicitous and terrible false faces, masques may serve cut-throats as well as the cemetery does; there are bag-snatchers out there, and whores...and revenants." (62)His exploration into masks and the people beneath them and what they reveal about Paris society of the time through his eyes is one of the reasons I am so in love with this author.

One more thing: among the stories here, there are a number in which the characters partake of ether as their drug of choice. That should come as no surprise, but what's interesting is that they seem to develop an acute awareness of just how damaging ether is to the mind and to the body. For me, these are some of the best tales in the book -- a bit self-reflexive, if you will.

I cannot explain why these stories fascinate me the way they do, but while I'm in his brain I don't want to leave. I know that sounds kind of strange, but it is what it is. It is a dark and dangerous place but for some reason, his work exerts some kind of bizarre pull that I can't resist.

Highly, beyond highly, recommended.