9781838396039

Egaeus Press, 2021

203 pp

hardcover

"this ice entombed wilderness has been driving people to the edge of madness for hundreds of years."

from "In Orbis Alius", by Colin Fisher

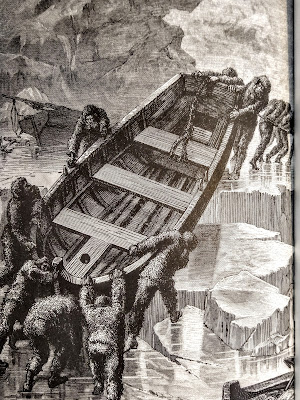

I happen to be a huge, huge fan of fiction set in the earth's polar regions, largely because I happen to be a huge, huge fan of nonfiction about polar exploration. That's been the case since like fourth grade, and unlike other interests that have come and gone in the meantime, that one is still going strong. Naturally, once I saw that Egaeus was publishing this book of strange tales set in the Arctic, it was a no-brainer -- this book had my name on it. Not only did I get my fill of Arctic weirdness, but the drawings inside that illustrate this anthology are also awesome. I am one of those strange people who will pore over a drawing like this one for a long time, trying to take in all of the detail.

|

from page 202

|

Opening the book just past the table of contents there first thing you see is a brief note:

"Herein are thirteen tales cast up in northern latitudes, hooked on the cardinal points of traitorous compasses. They are dark, strange, uncategorisable pieces, diverse in tone and theme, though each uniquely shaped by similarly restless Arctic tides, cold winds, and ancient ice-flows,"

and then it's on to the strangeness.

While everyone's mileage will of course vary, I did have more than a few favorites in this volume, beginning with "The Ghosts of the Great Northern Sea," by Leena Likitalo. As should happen in any anthology, this first story sets the tone for the rest of what's to come. A young woman named Soila finds herself strangely drawn to a stranger who has just arrived in her small village having traveled some two hundred miles on skates across the ice. She's not sure why until she learns about the provenance of the sweater he's wearing; wanting to settle certain questions in her mind, she decides she'll go back with him when he leaves. As they make their way across the ice, what happens on their journey will later become a "tale, and then a tall tale repeated around the fires when the wind howled outside," involving ghosts, murder, and above all, an unearthly justice. This story is so well done that I could completely picture it in my head. The next story, which is just as creepy as the first, is relayed via two sets of journal entries from 1926. In "The Tupilaq," by Stephen J. Clark, missionaries have arrived at Coral Harbour in Nunavut to "save these people from their primitive ways," and more importantly, "to make every conceivable effort" to convert the shaman, which would help in convincing the local population to "abandon their superstitions and embrace Christ as their saviour." However, the shaman, Iksivalaq, has been warned by the spirits that his rival Kulaserk knows of this plan, and that there are dire consequences in store should the missionaries succeed. All I will say about this one is that perhaps the missionaries shouldn't have been so quick to write off "pagan superstition." Number three is "In Orbis Alius" by Colin Fisher, in which Robson, an archaeologist working Viking settlements in southern Greenland, hears of the incredible discovery of an intact Viking ship on the northwest coast. By the time he actually arrives at Qaanaaaq station (formerly known as Thule) he discovers that two anthropologists Martin and Angela O'Brien, had been investigating, making three trips to the ship before Angela, for some inexplicable reason, "destroyed the site and the ship with it." Martin is nowhere to be found. When Robson begins listening to Angela tell her story, he believes she's become "unbalanced," especially when she starts talking about "Orbius Alius," which can mean "other Earth," "different place" or in Celtic lore, "Otherworld." While she won't really talk about what happened to her at the ship site, she has kept a record which Robson reads, a thoroughly fantastical but also thoroughly frightening account. In the meantime, strange things have started happening at the station that can't be written off as simple "mass hallucinations;" nor is it the case of being there in "this ice entombed wilderness" which has been "driving people to the edge of madness for hundreds of years."

|

another fine drawing ...

"

|

After the tension of the first eight stories, it was great to read Rhys Hughes' "

Ice Flows in Eden," which not only brought my pulse down but also made me laugh out loud. It all begins when an iceberg finds its way into the waters off Goa, and the two people who first spot it decide they need to take it back to the Arctic Circle where it belongs. Too much more would spoil the story, but it's a delightfully good one, perfectly placed in this book, allowing for breathing room after what had come before. The last two tales on my favorites list begin with Jonathan Wood's "

The Salon in the Woods," a tale of the "meeting of literary and spiritual minds" of two people (later joined by a third), who have isolated themselves from the rest of humanity in Russia looking to "write and compose and to unveil the Mysteries," to "construct that which will emerge out of nature..." I would absolutely love to read more by this author, whose prose is absolutely gorgeous. And finally, there's Alison Littlewood's "

The Light You Can Hear," in which a couple arrive at the Icehotel in Jukkasjärvi, Sweden, a Sámi word for "meeting place by the river." The couple are there "to escape, to be somewhere else,

something else, if only for a time." They are given room 215, the plaque outside of which reveals its name: "The Light You Can Hear." Inside there's a sort of "static crackle" as part of the ambience of "sounds from the Arctic landscape," which gives way to a

"soft, whistling, not quite like music, and something else: an almost unnoticeable breathy undercurrent, reminiscent of a voice."

It is the sound of the Northern Lights, according to the Sámi people, "the light you can hear;" they also believe that the Northern Lights are souls" that "bring the dead closer to us." But it's a trip to the nearby river that changes everything for this couple. This story may be short, but the writing is absolutely beautiful, capturing not only the place but also a keen and intense sense of loss.

I absolutely love the way in which these authors and some of those I didn't mention due to time considerations have incorporated local, indigenous lore and belief (real or imagined, I can't say for sure) into their work; as just two examples, Chris Kelso in his story "Blood-Sea" and the authors of "Oil," Sean and Rachel Qitsualik-Tinsley, do a great job in that regard. On the collection as a whole, well, you can't love all of them, but that doesn't mean that the stories I didn't mention weren't also worth reading. The Arctic has always seemed to me a mystical, eerie place, and each and every author in this book in his, her, or their own way somehow managed to capture that sense of otherworldliness in their work, as well as the effects of this place on the human psyche.

recommended.